Starting today — on what would have been his 81st birthday — and ending on Monday, Americans across the country remember one of the nation’s most influential leaders: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

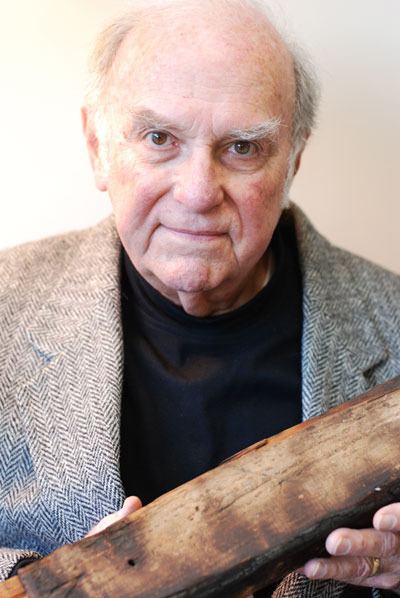

While the vast majority of us know him only through history books, photographs and a scratchy film clip of his “I Have a Dream” speech, there is a man on Mercer Island who knew the civil rights leader personally.

Robert Hughes worked side-by-side with King during the earliest days of the Civil Rights Movement in Montgomery, Alabama. The men worked together on the Alabama Council of Human Relations. Hughes, a minister himself, stepped in for King to lead his sermons at the Dexter Street Baptist Church while the activist was off leading marches. The two became close allies in the face of adversity.

Today Hughes is retired, living on First Hill with his wife, Dorothy, after a lifetime of working in civil rights; from first executive of the Alabama Council in 1954 to mediator of the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service’s Seattle branch in the early 1990s. Even now, the Islander continues to spread his message of equality — most recently speaking at the Mercer Island High School’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day student assembly and with the Mercer Island Reporter in an interview.

What was your involvement with the civil rights movement and how did you know Martin Luther King Jr.?

In 1954, at the age of 27, I was invited to serve as the first executive director of the Alabama Council of Human Relations. I was born and raised in Alabama. We set up office in Montgomery, in September of 1954, the same time that Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Montgomery as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

A major responsibility of mine was seeing over biracial organizations. Our aim was equal opportunity for all people of Alabama through action and education. It was a very small organization; about 75 people met together once a year. We served as a model for other communities — Birmingham, Mobile, and so on — and helped to establish channels of communication on biracial organizations. I asked Martin to act as vice president of human relations, and he accepted. He and his wife, Coretta, both became active in the Alabama Council.

What was it like, heading such an organization in the earliest days of the Civil Rights Movement? You must have really been sticking your neck out.

There was no acceptance whatsoever. This was the 1950s, not the 1960s. This was the only biracial organization in the state. Just as an example, it was strictly against the law to have integrated meetings because of the segregation laws. All of our meetings were integrated. The first meeting that we had, Martin served as vice chair and others — a Methodist minister, a political science professor, an official engineer with the state highway department, a seamstress — attended. That was the kind of mix we were trying to achieve.

This group, we had met together for almost eight months or more, when all of us were shocked to hear that one of our members — this seamstress I mentioned, she always sat in the third row on the left with her elderly mother, she was a very quiet, soft-spoken person — had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on one of the buses. That was Rosa Parks.

What compelled you to join the Alabama Council?

Well, I was invited. I had done some informal work as a United Methodist minister, and all of it in the area of human rights. They offered me the position to do this work, and I accepted. It was a full-time job — more than full time.

I was executive director until 1960, when we moved to Birmingham after the Montgomery bus boycott was successful. We were in good shape in Montgomery, and Birmingham was just the opposite; it was in terrible shape, so we moved there. There were 22 bombings of black-owned houses and places of business. All of the law enforcement agencies were infiltrated by the [Ku Klux] Klan. I traveled all over the state.

What are your memories of working with Martin Luther King Jr.?

After the bus boycott started in response to Mrs. Parks’ arrest, as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, Martin was needed to raise money for the carpool and operation of the boycott in northern states. So he invited me to preach for him several times at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church while he was gone.

We worked together. We traveled across the state to organize a biracial ministerial clergy group. That’s just one thing that comes to mind.

What was he like as a person?

He was a very quiet person; very outgoing. He had a ready smile. He would listen to you. He was interested in you. That was part of his nature.

From the beginning, there was a certain — I’m not sure how to describe it — but he was very wise in judgments and so on. We talked together about approaches that would be nonviolent.

Did you observe Martin Luther King Jr. grow more confident over the years?

Yes. By all means. He attracted the attention of notoriety. He was an exceptional person. He was one of the most inspiring speakers — clergy or otherwise — that I’ve ever heard.

When was the last time you saw him?

Well, the last time I saw him, he was lying in his casket. So that was in 1968 at his funeral.

You have been involved in civil rights for most of your life. What are some of the greatest accomplishments you’ve attained?

In 1960, I went to Southern Rhodesia in Africa as part of the struggle against apartheid there. It was under the white government — very oppressive. I spent five or six years there.

Getting back to the Alabama Council, up until 1960, just being able to organize local communities and establishing communication on the state level. If you recall, the ’50s were sort of a prelude to the ’60s in Birmingham with the fire hoses and the marches and so on. At the time, Birmingham was not seen as any more of a racist community than others in the South. But there was a lot that had been going on that was unrecognized or admitted.

Did you ever feel that your position on the Alabama Council put you and your family in danger?

We worked quietly on the council. But the Klan would come into the meetings and break them up. We had a cross-burning in front of our house in Birmingham.

Every Saturday night, the Klan would assemble 30-60 cars, all Klansmen, and ride to some target to burn a cross. One night, this would have been in 1959, I heard the horns blowing outside our house. We had just put our two baby daughters to bed, and I told my wife, “Here’s the Klan.” We looked out the front window and saw that long line of cars and pickup trucks. Some of them were erecting a six-foot cross in our front yard, and they set it on fire. They got back in their cars and slowly drove off yelling.

The objective was terrorism, of course. Well, I had a message for the Klan too: As terrorists, you’re a failure. Dotty and I went out to the street and waved to all these people as they drove by. We got a garden hose and started spraying water on the cross to put out the flames. As I was spraying, I’m sure I got some Klansmen doused in the process. It was very nonviolent, you understand.

Looking back at the civil rights movement now, so many years later, what do you have to say about how far we’ve come?

We’ve got a long way to go. That’s my first answer. Obviously, we’ve made progress. [During the 1950s] I don’t think that the general white population of the United States had any perception of the tremendous gulf that separated blacks and whites. Yes, we’ve made progress through civil rights agencies, education and so on. Through the sacrifices of many, many people who were inspired by Dr. King — black and white. But we’ve got a lot of progress yet to go.

The people of Seattle need to realize that there are still racial issues here — racial profiling, for example — that need to be addressed. Racial profiling in law enforcement agencies is a common complaint. So much of the data that is collected shows that there are racial disparities today. We need to maintain close attention to these disparities, continue establishing communication about them and work to resolve racial issues when they do arise.

What is the message you would like to get across to today’s youth, who did not experience the Civil Rights Movement?

We are standing on the shoulders of a whole line of others who have preceded us; people like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, who have now passed on. But the task is not finished. For all of their sacrifices, there are other areas where those same lessons — not just on race, but sexual orientation and religion, such as the Muslim communities that are victims of prejudice — need to be applied today.