On June 8, Mercer Island resident Judy Kusakabe spoke to all 4th grade and some 5th grade students at West Mercer Elementary School to tell them about her family’s experience being incarcerated in a prison camp during World War II because they were Japanese American.

“It was the first time young children were imprisoned by America,” she said.

From 1942-1945, approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to prison camps in response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan.

Nicholas Viafore, age 10, 4th grader at West Mercer Elementary School, said, “I learned that during WWII many Japanese Americans were treated unfairly because they were suspected of being spies even when no evidence was found.”

This past month, Kusakabe visited all of the 4th grade classrooms in the Mercer Island School District; but she has been speaking to students in the district about her family’s experience for over 15 years. This year, she has spoken to 700-800 people, including students in Mercer Island and other school districts.

“It fuels me on and I appreciate that kids get it and understand the importance of kindness,” Kusakabe said.

Besides caring for her family, her mission in life is to teach people about her family and friends’ experience during WWII. Nidoto Wai Yoni, a Japanese term means “Let it not happen again.”

Her parents and other families never talked about their painful experience, but she is here to tell their stories because “the more people hear about it, the less chance this can happen again.”

“It is very important for students to hear Judy’s story as it helps them realize that this is living history connected to someone they know and not just some event they read about in a textbook,” said West Mercer Elementary 4th grade teacher Sherry Isaacs. “As a result, they are more engaged and interested in learning about how we can be better citizens of the world and not have history be repeated.”

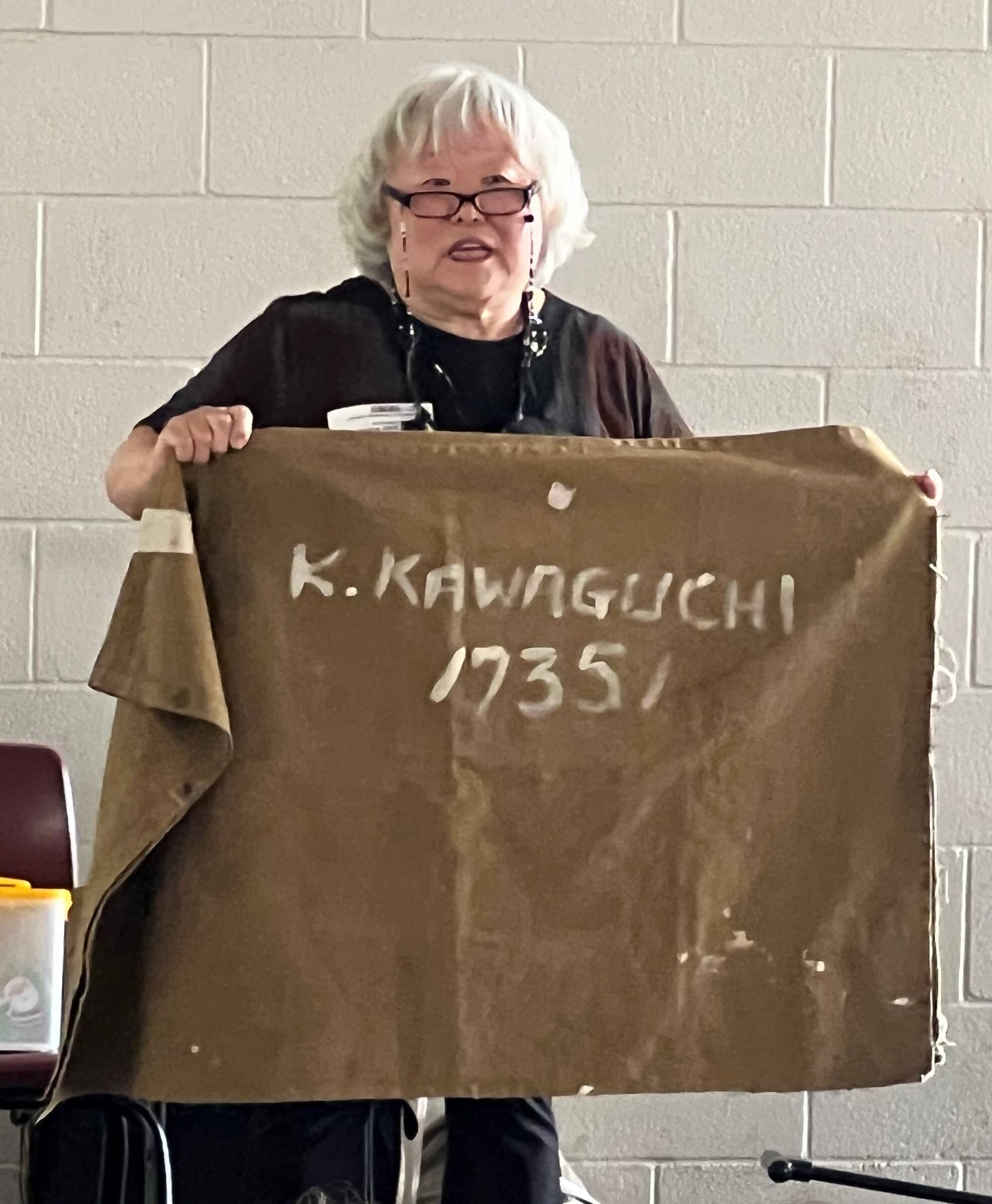

During her presentation, she has many stories and family artifacts to share. There is the family gunny sack and basket, where her family had to place all of their belongings when they were sent to the prison camp. Every family had a number and you had to wear a tag with your number on it. She shows replicas and pictures of inhumane living conditions, including cramped bunkers, no running water in the family living areas, and guard towers.

“We lost our dignity along with our liberty,” she explains.

She tells other stories too, like her friend Pat who was 8 years old when her father said they were going camping. Pat was so excited that she told her best friend Charlie about her trip and that she would see him when she returned. She saw her father cry for the first time, not knowing that they were really going to a prison camp. She never saw Charlie again.

Her uncle, Mike Kawaguchi, an illustrator at Disney who worked on Bambi and Fantasia, was in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a group of Japanese American soldiers who fought in WWII and was one of the most decorated fighting units in US military history. She said, “They came back in glory and brought honor back to their families.”

Eighty years ago, Kusakabe’s mother was pregnant with her while she and her husband were imprisoned on the Puyallup Fairgrounds during World War II. As a baby, they lived in a tiny barrack under the ferris wheel; but they were one of the lucky ones – others had to live in the filthy and smelly horse stalls. Soon, her family was sent to Camp Minidoka in Idaho and eventually came back to Seattle in 1945. Before incarceration, her father and his business partner had to sell their fuel business, “Tokyo Fuel,” for “basically nothing” and after their return to Seattle, her father never owned a business again. He always had to work for someone else and work even harder to prove he was a good American.

“Eventually he got the apology and my father felt free,” she said about the Civil Liberties Act passed by Congress that gave reparations and a formal apology to surviving Japanese Americans who lived through the incarceration during WWII.

Kusakabe has lived on Mercer Island for 50 years and moved here after she faced discrimination in a different city. She said she and her family have not experienced discrimination on Mercer Island. She is a retired therapeutic dietitian and has other ties to the school district — first as a food cook in the late 1970s, then interim dietician and later as a paraprofessional. Her three children went to Mercer Island schools and four of her grandchildren live on Mercer Island.

She was going to stop making presentations two years ago, but decided to continue after the rise of anti-Asian violence and discrimination.

“I want to do it until I can’t do it anymore,” she said about her presentations and hopes that others will continue to tell her story when she is not able to.

Many were moved by her presentation, including Emerson Crespi, age 9, 4th grader at West Mercer Elementary School. He told his mother, Jennifer Crespi, “l listened to the saddest stories I’ve ever heard in my life. Families were forced to move from their homes and had to leave their pets behind. They had no choice! Can you imagine what it would be like to have to leave the pets that you love so much and never see them again?”

Megan Isakson, principal at West Mercer Elementary, said, “Stories are such a dynamic way to connect, humanize, and learn about our history. Judy’s work and her commitment to sharing her family story of imprisonment is so important for our scholars, as it provides such a powerful, personal lens to a piece of our history. Our scholars were given the opportunity to move beyond a text or media account of the imprisonment of Japanese Americans in the United States, and connect with Judy and her first-hand account of her life and family experience. It is crucial we learn about our past, including objectionable events of the past, in order to learn, grow, and impact positive change as a society.”

Evan Manfredo, age 10, 4th grader at West Mercer Elementary School, said that he is “glad I learned about it and got to meet her.”

Kusakabe ends her presentation by giving each student two paper cranes – one for them to keep to remember what she told them and another to give to someone out of kindness or thankfulness. She hand makes 1,000 cranes before her presentations and said, “If you make 1,000 cranes, your wish comes true.”