Although he’s been retired for over 25 years, Dr. Al Skinner remains a doctor through and through. Sit him down, and the first thing he’ll talk about is immunizations.

He knows their effectiveness, and wants to make sure younger generations understand the seriousness of the diseases immunizations help prevent, like polio, tetanus and measles. He emphasizes scientific fact disproves any potential link between vaccinations and autism.

“Today’s vaccinations have been carefully studied, and they are a wonderful advance in health for children and adults,” Skinner said.

He would know; he has pediatric experience dating back 60 years.

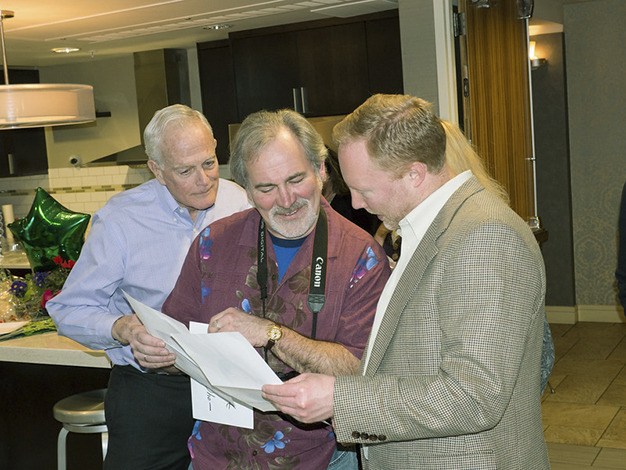

Skinner was among some 20 pediatricians, nurses and employees of Mercer Island Pediatrics and Puget Sound Behavioral Medicine who came together Feb. 15 at the Mercer Apartments to celebrate 60 years of pediatrics on the Island.

The event was organized by retired physician Dr. Janice Woolley, who practiced for over 30 years, primarily on Mercer Island.

“I’ve been retired a few years, dealing with health issues and writing my life history, and I was thinking of all the people I’ve worked with over the years,” Woolley told the Reporter. “I thought, ‘Gosh, I should get together with them.’ They were all interested, and it went from there.”

Skinner, 90, was right at the forefront, opening his practice in 1955, seven years after the first doctor on Mercer Island, Dr. Howard Eddy, began making house visits. Skinner came to the Pacific Northwest by way of Boston, working an internship at Harborview after attending med school at Harvard. He heard about Seattle from a friend in the Navy, where he served for over three years during World War II.

While at Harborview, Skinner frequently went on weekend camping trips with his growing family, and in turn fell in love with the area. After a trip back to Boston in 1952 to finish his residency, Skinner came back the next year to work as chief resident at the Children’s Hospital. He opened his practice after doing a fellowship year in 1954 with Belding Scribner.

“There were large open spaces here in the business district,” Skinner recalled. “The population, if I remember correctly, the census showed 5000 inhabitants of Mercer Island in 1950. It was not enough to support a practice. But people are referred by word of mouth.”

Skinner said about half of his patients came from off-Island, either by the then US-10 highway or by ferry. Welfare patients would be referred from South King County. People who had moved off-Island would come back for healthcare, from as far as Alaska and eastward beyond Cle Elum. After a couple years of practice, Skinner managed to accumulate more patients on the Island.

“They were our neighbors and friends, people we were in the bowling league with and people we saw in the PTA,” Skinner said of his patients. “I was a convenient doctor on the Island and a lot of people don’t like to cross the bridge if they don’t have to.”

Front row, from left: Dr. Luz Gonzalez, Gail Provo, Dr. Jan Woolley, Dr. Al Skinner, Dr. Danette Glassy and Cheri Zavaglia. Back row, from left: Cathy Hummel, Peggy Way, Dr. Hal Quinn, Dr. John Schreuder, Dr. Ted Mandelkorn, Dr. Julie Ellner, Julie McAllister, Yin Chan and Becky Powell (Jack Woolley/Contributed Photo).

Pediatrician Dr. Hal Quinn, who has practiced on the Island for 28 years, said he was pleased to see all of his former partners in one place. He said practicing in a small community like Mercer Island offered practitioners a unique opportunity to know their patients in a deeper way.

“I’m on my second generation of patients now, so I’ve got people I’ve taken care of mostly as teens that I inherited from my former partners,” Quinn said. “They move off-Island and then come back and are bringing their children to me, so that’s really cool.

“In general, pediatrics is a great field. We all have days where we get up on the wrong side of the bed so to speak, and then come in and see kids and they’re so alive and so fun. They smile, they interact, they’re resilient, they’re just great. It is so fun to take care of a patient population that is just the way children are.”

Woolley was a trailblazer in her own right when she began practicing in 1970. She said only eight percent of physicians were female when she began med school in 1962, and there weren’t many other options for female doctors on Mercer Island.

“I think I was the first,” said Woolley, who practiced for over 30 years. “There were other female physicians in the Greater Seattle area, but I was it on the Island.”

Woolley said she’d connect with a group of women who practiced in other areas, getting together for lunch about once a month and network.

“There were some things unique for us, with parenting responsibilities and balancing everything,” she said. “My own mother wasn’t employed outside of our home, so I was kind of figuring that out, too. My husband has always been tremendously supportive. He was the one who was the parent when I was on call and got called away.”

Skinner thought girls on the Island appreciated having a female doctor available, and Woolley agreed.

“I would like to think it was a good influence. Some of my former patients have gone into medicine, which was rewarding for me,” Woolley said, noting Island dermatologist Dr. Allison Hughes was one of her patients.

But it was the special relationships Woolley cultivated with children and families that she found most rewarding from her work.

“I think peoples’ stories have always interested me, and really getting well-acquainted with the families is sort of the story of their lives and their children’s lives,” she said. “I felt really honored to be privy to some of their private moments and be helpful in times of crisis.”

Among the changes Skinner has seen in his 60 years on the Island, he mentioned a greater deal of ethnic diversity and said there were more “one percenters” on the Island these days. He still lives in the North-end house he had built in 1962, which he describes as “a daylight basement and a loft,” where he takes care of his 95-year-old wife, Sarah. The couple will celebrate 64 years of marriage this month.

Coming from a family of teachers, Skinner said similar to a teacher, working as a pediatrician gave a certain kind of satisfaction out of the role he played in a child’s life and in a family’s life.

“I was in the grocery store and [there was] a mother and a small child, about four years old. The mother said, ‘Eddie, say hello to Dr. Skinner.’ Eddie looked up at me and said, ‘No, Dr. Skinner is in his office,'” Skinner recalled with a laugh.

“There were sad moments as well, where things didn’t go well. At any rate, it was a very satisfying career and I’m glad I did it.”