Kirkland resident Tami Werenka found her son Seth on a Sunday morning. It was time for church, and her phone calls to him went unanswered. She grew worried and gave permission to his landlord to check in on him by entering his apartment.

He was already dead by the time they found him, she shared. He had passed away earlier that morning after an accidental methadone overdose.

It was the last day of the year, in 2017. And for Seth, the last of his life.

Werenka shared her son’s story during an announcement by state attorney general Bob Ferguson on Mar. 12. Ferguson filed a lawsuit against the three largest distributors of prescription opioids in the state. He argues the distributors failed to alert law enforcement of suspicious orders, illegally shipped the orders and for years helped fuel the state’s opioid epidemic.

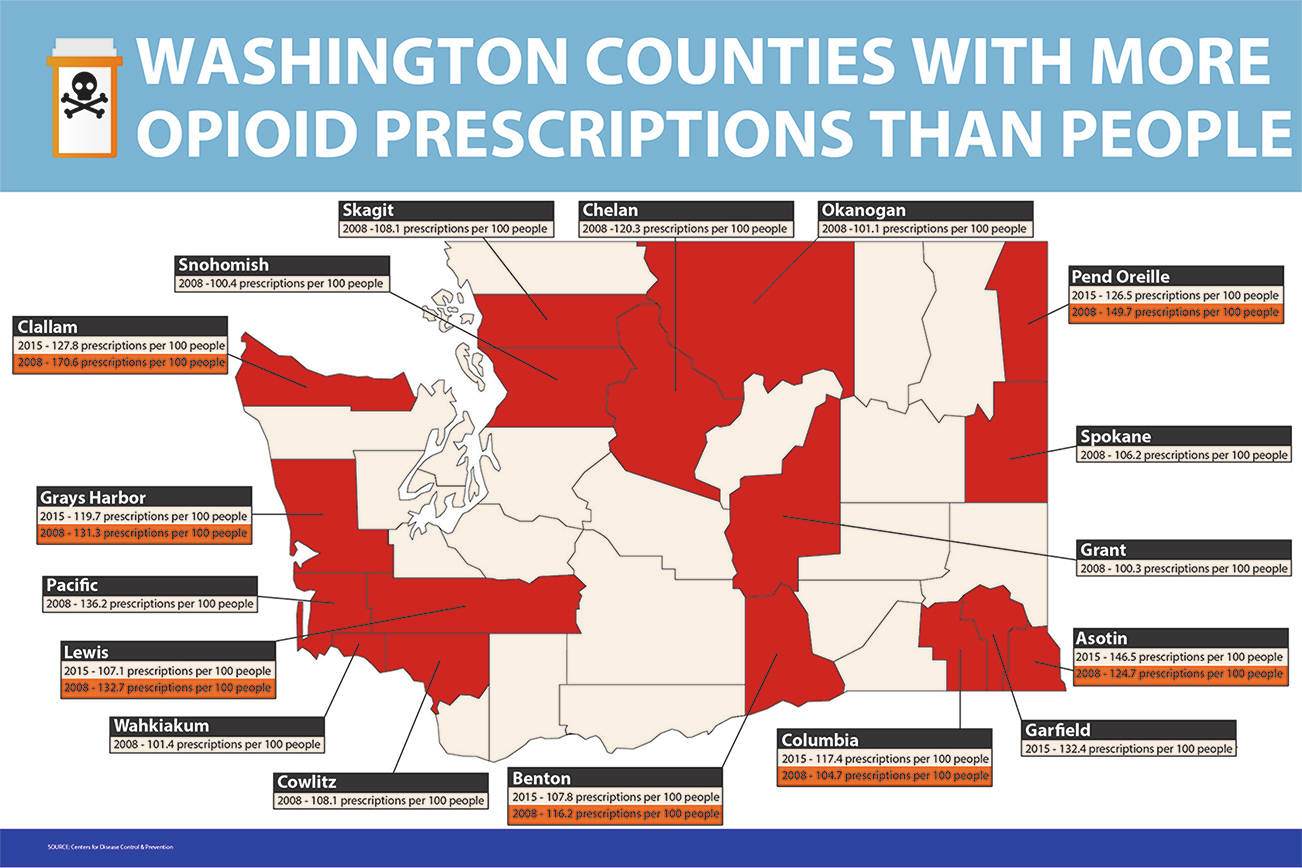

Between 1997 and 2011, both prescriptions and sales of opioids in Washington grew more than 500 percent. And between 2006 and 2017, overdoses from these drugs killed more than 8,000 state residents, Ferguson’s office reported. Ferguson is seeking penalties and damages.

The lawsuit, filed in King County Superior Court, is against McKesson Corp., Cardinal Health Inc. and AmerisourceBergen Drug Corp. The lawsuit alleges these companies shipped large amounts of fentanyl, hydrocodone and other prescription opioids into the state when they were aware the drugs would likely end up in the hands of addicts.

The government requires distributors to monitor the size and frequency of opioid orders, reporting any that are suspicious that could potentially end up in the illegal drug market. They are required to stop these shipments and report them to the Drug Enforcement Agency. Instead, these distributors did not stop the shipments or report them and have continued to shell out millions in fines.

“We are woefully under-resourced when it comes to treatment. The people who are responsible for this epidemic should begin paying for it,” Ferguson said in a press release. “We are going to hold these companies accountable and get more money into our communities for treatment.”

Between 2006 and 2014, the three named companies supplied more than two billion opioid pills to Washington, according to numbers released by the Ferguson. During certain years, distributors shipped enough opioids to supply every resident in certain counties with dozens of pills. Based on a conservative calculation, Ferguson’s office said the defendants shipped more than 250,000 suspicious orders into Washington from 2006-14.

In response to the lawsuit, John Parker, senior vice president of Healthcare Distribution Alliance said that distributors should not be to blame for the epidemic.

“The misuse and abuse of prescription opioids is a complex public health challenge that requires a collaborative and systemic response that engages all stakeholders,” Parker said. “Given our role, the idea that distributors are responsible for the number of opioid prescriptions written defies common sense and lacks understanding of how the pharmaceutical supply chain actually works and is regulated. Those bringing lawsuits would be better served addressing the root causes, rather than trying to redirect blame through litigation.”

Seth’s story

Seth became addicted to methadone — a synthetic opioid — while experimenting with drugs as a youth. He started dabbling in drugs at 13. First he smoked marijuana with some friends. This evolved to getting pills from friends at age 16. His drug of choice was methadone.

“Before long he was getting so dependent he needed it every day to make it through the day,” Werenka said.

At 17, Seth’s grandfather persuaded him into starting at a methadone clinic. These clinics are used to help wean people off of heroin and prescription painkillers through replacement therapy as people are given low doses of methadone.

But Seth’s efforts were fruitless. And his addiction began to run his life.

“It was the first thing he thought of when he got up in the morning and the last thing he thought of when he went to bed,” Werenka said.

The addiction took its toll on Seth’s body. All of his teeth were pulled as a result of negligence from living on the streets. In addition, he was hospitalized many times.

Seth started to turn things around in the last five years of his life. He found salvation, Werenka said, and gave his life to Jesus Christ. His goal of getting off the drugs were renewed and he went to five different clinics from Everett to South Seattle.

And they learned, after a Harborview Hospital visit, that Seth, having been on methadone for more than five years, was likely what the doctor called a “lifer” — someone who would likely never come off the drug.

“We all make choices,” Werenka said. “We sometimes get stuck in a situation. They went too far in life. It got hard and actually it wasn’t fun doing drugs anymore because actually it got you addicted.”

Seth’s high tolerance level, meant the small doses offered at the clinics didn’t cut it. He would encounter pain, leave and end up back on the street.

Before he died, Seth shared a message with his mom: “Warn people if they’re going into a methadone clinic, please don’t go. It’ll ruin your life. It’s so much harder to get off of that than the heroine.”