A new book, “Burning Forest, the Art of Maria Frank Abrams,” describes the remarkable life and work of a modernist artist and Island resident. It is long overdue.

The large format and richly done 9-by-12-inch book, which includes dozens of images of her paintings and mosaics, was written by Seattle-based Matthew Kangas, a longtime art critic, curator and author. The book is not only about Abrams’ art but the life of the Island artist, a Hungarian native who was imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps in the 1940s.

And who is Maria Frank Abrams? You already know. You have seen her art. It is at the Mercer Island library, at the Seattle Art Museum, at the Henry at UW. There is a piece in the King County Courthouse, at city offices in Seattle, Harborview Medical Center, the Kline Galland Home and now at the Jundt Art Museum at Gonzaga University in Spokane.

Abrams and her husband of nearly 60 years, Sydney Abrams, have lived on Mercer Island since the mid-1950s near West Mercer Elementary School. They have a grown son and a grandson who both live in Israel.

To summarize her story in just a few sentences is to risk trivializing a life and time that combines the best and the very, very worst of the world in the 20th century.

Abrams, now 86, grew up in Debrecen, Hungary, as the Nazi presence overwhelmed the country in the 1930s. A Jew, she was just 20 and already an artist when she and her family were taken to concentration camps. Her parents and all of her extended family except herself and a cousin were killed. Three years after her release from the camps, she found her way to Seattle on a Hillel scholarship to study art at the University of Washington. At the UW, she studied under renowned artists such as Walter Isaacs and Mark Tobey, and those associated with the growing modernist art movement. It set her on the path to her own unique style.

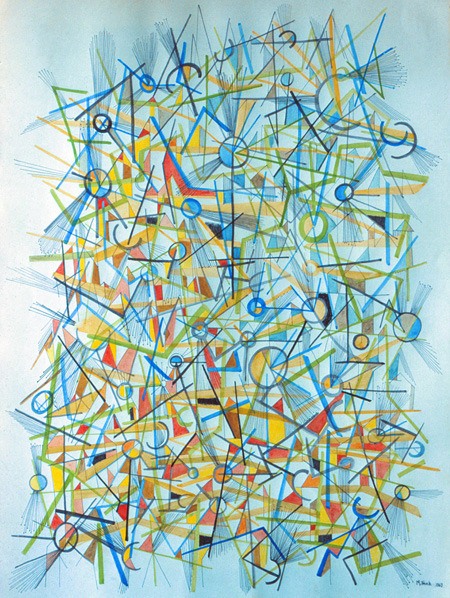

Her style is “representational and abstract imagery,” including landscapes and always the sky as subjects. They rarely show faces or figures. But they are not needed. The works are geometric, layered, textured paintings or mosaics that at first might seem dark or ominous, yet with her shrewd use of light, they depict ethereal scenes filled with movement. They breathe land and sky and emotion.

On a rainy afternoon at her home, Abrams, small and slender, is impeccably dressed in a warm, stylish blazer and wool slacks with a cup of coffee balanced in her lap. She looks younger than her 86 years. She is unable to paint now, but her studio remains intact at her home. Expanded several years ago, it has high ceilings and large windows facing west into the greenery and sunsets over the lake. Her tools and brushes remain at the ready. Stored within the space are dozens and dozens of finished paintings. Many fill the walls and along with them are objects both primitive and fine, lining shelves and tables. She runs her fingers over them quietly. Just inside the door from a deck is a table top filled with rocks and shells. They are raw and unpolished, but curiously, sorted into groups. Both she and Sydney pick up the stones wherever they go — a habit they each have. The shiny, pretty shells are mostly her husband’s, and the textured, mostly gray oval rocks are hers.

Kangas and others who have reviewed her work find images of the camps, smoky skies and unspeakable loss and horror. But both she, in past interviews, and her husband who now speaks for her, are chagrined that her work is viewed primarily through the lens of her Holocaust experience. She has long insisted that it is her life in the Northwest and its gray “healing” light, far from her ancestral home, that has formed her art. She wants to talk about the light and beauty that she has found here. When asked for more insight, she points to outside her window into the steely tinge of the clouds. Perhaps anticipating further questions about the influence of the Holocaust on her art, she turns with a direct look and makes it clear that her life has been more than that. “I have lived a long time,” she begins.

How and when she painted perhaps shows her comfort with the dark and her appreciation for light. “She painted at night and late into the night,” Sydney Abrams said. When asked why, she is surprised by such a question. “It is a good time to work,” she said.

Her eyes widen in dismay if she decides that her husband needs to be corrected on a point. Despite her diminished ability to find the words she wants to use, she appears to know well who she is and what her work means.

“I know what it is about,” she said about a painting more than once. “It is mine.”

“Burning Forest”

“Burning Forest: The Art of Maria Frank Abrams,” by Matthew Kangas, is available for sale at Island Books at 3014 78th Ave. S.E. on Mercer Island. The hardbound book has more than 25 plates of her original work. It was published by the Museum of Northwest Art. It retails for $40.