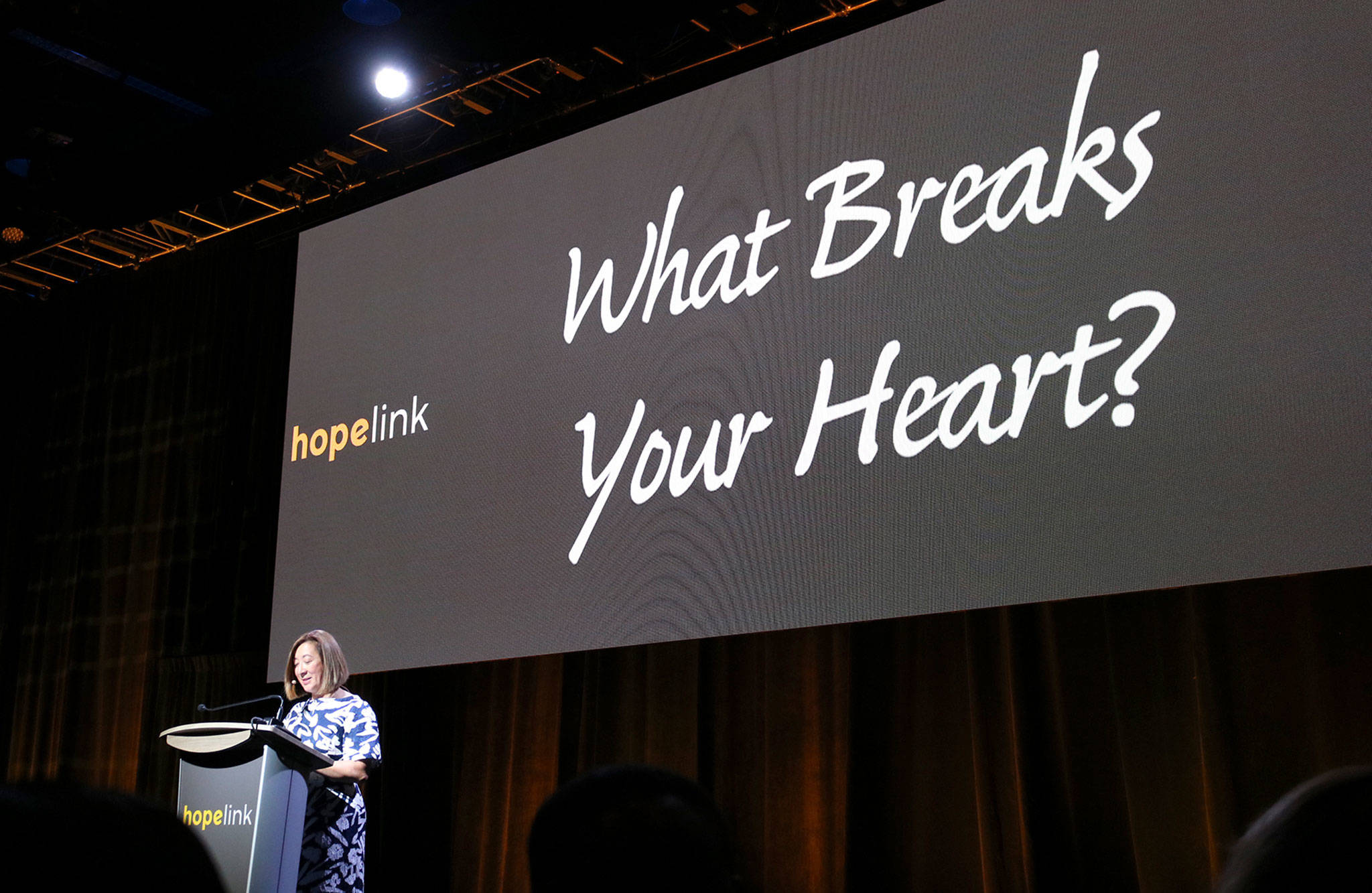

Before introducing the featured and keynote speakers at Hopelink’s 23rd annual Reaching Out luncheon, held Oct. 15 at the Meydenbauer Center in Bellevue, the nonprofit’s CEO Lauren Thomas asked attendees to consider one question: “What breaks your heart?”

For the donors and supporters at the event, it’s the 86,000 people (one in seven) in north and east King County currently living in poverty.

Hopelink raised more than $930,000 at its luncheon to help people achieve stability and exit poverty. Hopelink has many facilities in the area — including Bellevue, Kirkland, Shoreline, Sno-Valley and Redmond — and provides many services, including food assistance, employment services, emergency financial help, housing, transportation, adult education, financial capabilities, energy assistance and family development.

At the luncheon, Thomas announced that Hopelink had reached its fundraising goal of $20 million in the first phase of its capital Campaign for Lasting Change.

Hopelink’s mission “speaks to my life on many, many levels,” keynote speaker Dr. Tererai Trent told the Reporter in an interview after the luncheon.

“We live in societies that ignore those that fall under the cracks, but then you find organizations like Hopelink say, ‘You know what? That’s not going to happen on our watch,’” she added.

Trent’s life has been about redefining the narratives that are passed on to future generations. She was born in a war-torn village in Zimbabwe, and came from a long line of “women who married young, before they could define their dreams.” As a young girl, she watched the cycle of poverty silence the women around her.

“I always visualize my great grandmother. When she was born, she was born into this relay of poverty and holding the baton, and she ran so fast with this baton, the baton of illiteracy, the baton of early marriage…and handed it over to my grandmother,” she said.

Trent’s grandmother passed it on to her mother, who passed it on to her. Trent found herself a wife and mother of three children at age 18, with only one year of schooling. But she dreamed of a better life.

“I never wanted to be part of that baton,” she said. “It’s not my race. It’s not my baton. I didn’t want to pass that on the next generation, to my own girls…But unfortunately, I was too poor. I grabbed it.”

Trent wanted to come to the United States and get an education — a GED, a bachelor’s degree, a master’s and a PhD — and was inspired by other educated women, including the CEO and president of Heifer International, who told her “it is achievable.” Her mother told her to write her dreams on a scrap of paper and bury them in a tin can in the ground, but first, to add a fifth goal: to give back.

“Your dreams will have greater meaning when they are tied to the betterment of your community,” Trent’s mother said.

Today, Trent holds a professorial position at Drexel University School of Public Health and is an internationally recognized advocate for social change. She founded Tererai Trent International, and with the help of Oprah Winfrey and Save the Children, is on a mission to provide universal access to quality education while also empowering rural communities. Winfrey donated $1.5 million to fund that fifth, “sacred,” goal, and together they’ve built 11 schools benefiting more than 6,000 girls and boys, Trent said.

It took her a long time to achieve her goals: eight years to get equivalent of a GED and then 10 more at Oklahoma State University and Western Michigan University, where she earned her master’s and doctoral degrees.

While in Oklahoma, Trent and her family lived in a trailer home and ate fruits and vegetables from the garbage can of a local grocery store, she said. Hearing the testimonials of Hopelink clients that were in similar situations “took me back,” she told the Reporter.

Ronald George also shared his family’s story at the luncheon. George owned a business with his father, but was unable to keep it afloat after his dad died. His family became homeless, and he, his wife and their two children started sleeping in their car. They were cold, hungry and living in “survival mode,” George said. When Hopelink called and said they had space in their shelter, it felt “like a miracle.”

Hopelink helped George’s family get back on their feet, and the “end of homelessness was just beginning of [their] new lives” and a “chance to build a stronger foundation,” George said. He took a part time job at Hopelink’s food bank in Kirkland, later becoming the warehouse coordinator and as of a few weeks ago, the supervisor.

“When Thanksgiving comes around, I love giving turkeys and chickens to families who wouldn’t have a meal if not for Hopelink,” he said. “I remember a day when all we had to eat on Thanksgiving was a head of lettuce…It makes me happy to know that Hopelink is there for families who are hungry, like we were.”

Jeff, Lynette and Zelda Shirk, who chaired this year’s luncheon, said that Hopelink is like a family.

Trent said that she was able to make it through hard times in her life because she was able to ask for help, “to show vulnerability.” Still, she noted that “you can only take that first step when you know the person in front of you is willing to receive you.”

“If we give opportunities to those who are poor, who are suffering, they can achieve their dignity,” she said. “It’s all about how we come together as a community.”

Success is not about personal goals, money, diplomas or trophies, she said, but about how a person’s achievements are tied to the greater good. Trent said she was drawn to Hopelink’s mission to provide services, but more importantly, dignity, to those in need. If the next generation can “run with a different baton,” she said, “we can live in a society without poverty, without hunger.”

The funds from Hopelink’s capital campaign will go toward renovating the organization’s shelter in Kenmore, building new service centers in Redmond and Shoreline and expanding its food program to serve an additional 6,000 people by 2020.

See www.hopelink.org for more.