At their April 6 meeting, Mercer Island Chamber of Commerce members learned how their tax dollars are spent — and saved — on criminal justice.

King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg outlined 10 ways his office is seeking to reform the system. This is warranted not only on a philosophical level, but also a practical one: Washington’s prison are at capacity, and no one wants to build a new one, Satterberg said. Each new prison costs $250 million to build, and $80 million per year to operate.

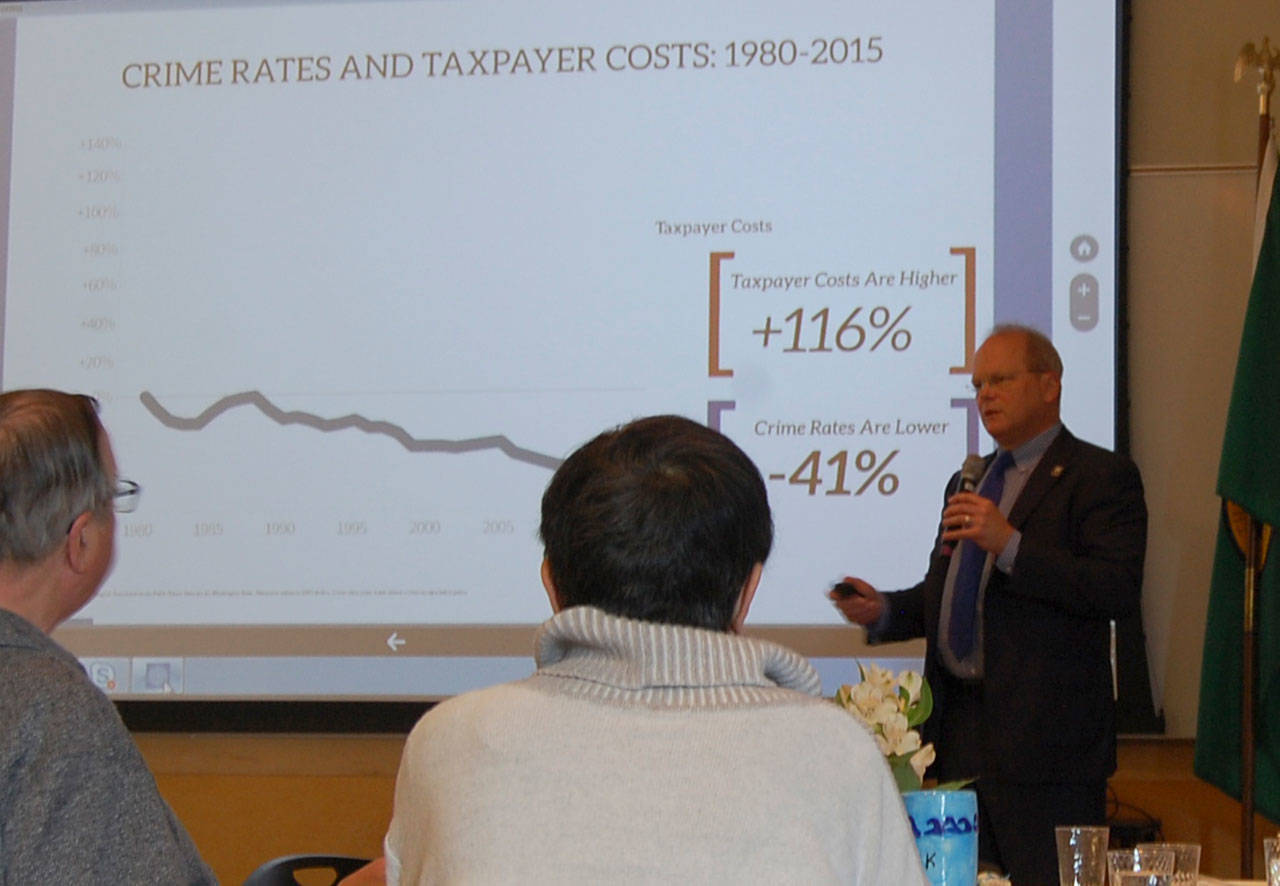

Satterberg’s office has pioneered some programs that aim to divert people from the “very expensive” criminal justice system, saving lives and saving money through “restorative justice” and “community justice.”

“Helping people, rather than punishing people, actually works,” Satterberg said.

The best thing to do to divert people from the system is to graduate more students, he said, calling education a “protective blanket.” Three out of four inmates in Washington state prison dropped out of high school, and youths who drop out of high school are five times more likely to go to prison during their lifetimes than those who graduate.

Satterberg said that “exclusion” policies can contribute to the problem, and that alternative programs are needed to combat truancy and the “school-to-prison pipeline.” For example, in his home school district of Highline, students who are expelled from high school are offered a seat in a community college.

Over the years, King County has implemented a wide range of diversion and community-based programs to hold young offenders accountable outside the court system, including the 180 Program, which gives minors accused of misdemeanor offenses a chance to have their charges waived. It diverts 400 youth per year, Satterberg said.

He also said that the racial disproportionality in the criminal justice system needs to be discussed. African Americans make up 4 percent of the Washington state population, but 18 percent of its prison population. Addressing that disparity will help build trust between law enforcement and communities, Satterberg said.

Satterberg promotes the idea of “community justice,” which means “engaging community leaders in an effort to define accountability and devise alternatives to the criminal courts for the complex social problems that have historically been dumped onto the courthouse steps,” including school discipline, drug addiction and mental illness.

“Nationally, for each person who’s seriously mentally ill, who’s in a state-funded psychiatric hospital, there are 10 in state prison,” Satterberg said. “And we know the other default system is the streets, the tents, the overpasses, the homeless encampments. Serious mental illness goes along with serious drug addiction, and we’ve made the decision over time to not invest in the kind of community-based treatment that can help people.”

Six years ago, Seattle piloted a program that has since become a national model: Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD). It helps break the cycle of incarceration for nonviolent drug offenders by connecting them to services that help with problems such as homelessness and addiction, offering them an option beyond jail.

Recently, King County set up a task force to look at opioid issues. They came up with 30 recommendations, the most controversial of which was supervised sites for drug consumption. Satterberg said that addiction is a complicated issue, but that “the opposite isn’t sobriety, it’s connection” with their families, friends and communities.

Satterberg’s office is also working on a “familiar faces” program, where social workers will offer services to people who are frequently and repeatedly booked into jail for minor offenses.

Other reforms include: expanding clemency and second look programs, improving prison outcomes, supporting reentry, continuing sentencing reform and teaching violence prevention.

For more, see www.kingcounty.gov/depts/prosecutor.aspx.