Was the war like this? Lori Lake asked her father, Roy Mays, at the movie “Flags of Our Fathers.” Yes, he said, it was.

The movie depicted the Battle of Iwo Jima and the first time an American flag was unfurled in Japanese-occupied territory. Five Marines and a sailor raised the flag on Mount Suribachi during the battle, and the moment was forever immortalized in the famous photograph that inspired the Iwo Jima memorial.

The movie gave Mays a platform from which to start talking about his own war experiences, Lake said.

Mays was a private first class sharpshooter stationed in a Marine detachment on board the USS Idaho battleship, in the heart of the Pacific Theater.

“We saw the flag go up on Mount Suribachi,” Mays said. “Everybody was clapping and yelling like mad.”

His battleship was firing close to the island when the flag was raised.

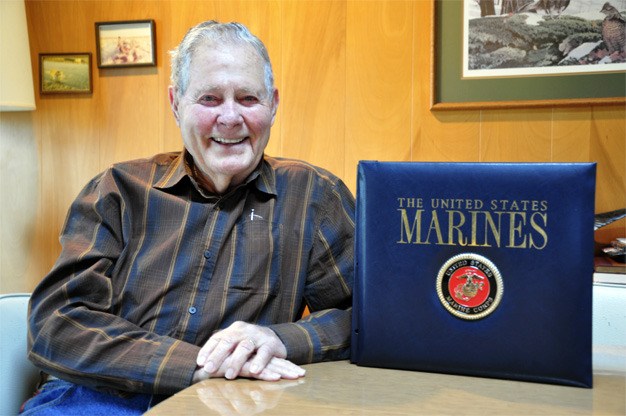

A longtime Mercer Island resident, Mays recently celebrated his 90th birthday on Oct. 23 with family and friends.

Mays enlisted in the Marine Corps in Houston, Texas, within two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He boarded a train to boot camp in San Diego with his nephew and a friend, who were both sent home because of poor eyesight. Infantry, artillery, or “C” school: the choice was his. He entered “C” school, graduated, and went aboard the USS Idaho from pier 7 in San Francisco.

The battleship practiced up and down the coast, then sailed to Hawaii, before entering combat.

“When I saw Pearl Harbor, I thought, boy, I remember studying the Hundred Years War in school,” Mays said. “I thought it was going to be another Hundred Years War. Fortunately, it wasn’t.”

It was in Hawaii where Mays crossed paths with two of his brothers: James and John, who were also in the service. Their hometown newspaper published a story about the unexpected reunion.

“It was such a surprise, a complete surprise. I didn’t expect to see them during the war,” said Mays. John was assigned to a submarine, and James was stationed on a destroyer.

Mays grew up with nine siblings on a cotton farm in Groesbeck, Texas, before the family moved to Tulsa, Okla. Those were the Depression days, when the children would pick cotton for a penny per pound.

In October 1942, Mays landed in Seattle. His battleship was being reoutfitted in Bremerton. At the Trianon Ballroom on 3rd and Wall, where the big bands played and there were dances every night, he met the woman who would become his wife: Maizie Fisher. They met on his 21st birthday, and she wrote letters to him nearly every day for the next three years. They were married in August 1945, after the war ended.

Mays’ first campaign with the USS Idaho happened at Attu and Kiska in the Aleutian Islands in 1943. From there: Makin, Gilbert Islands; Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands; Kavieng, New Ireland; Peleliu, Palau Islands; Saipan and Guam, Marianas Islands; Iwo Jima; Okinawa, and the Philippines.

“I had a front row seat for all of World War Two,” Mays said, “watching all the landing craft go ashore, and thousands of ships, supply ships, support ships, taking them into the landing, airplanes going in and out, bombing where they could, and ships firing.”

The big ships would fire on the Japanese-occupied islands as airplanes dropped bombs.

“We would see all the troop ships come in, and they would start out in their landing craft, and it all began,” Mays said.

“Iwo Jima, in the Volcano Islands — that’s where most of our problems began on the battleship. Japan was unloading all the airplanes, the suicide planes, kamikazes, they called them. They had the skies full,” he said. “I was in a quad-4 millimeter battery firing at the suicide planes and on the islands as well.”

They shot down nine enemy planes. But at Okinawa, the ship took a hit. A kamikaze left a 40-foot hole directly below Mays’ battery.

“I could see him coming right at us. I controlled the firing,” Mays said. “Everybody just dropped as he hit the ship at the water line, and a great big flood of water came up.”

The gunners below Mays were completely submerged, but all surfaced unharmed. No one was killed.

More than 60 years later, Mays’ family took him to Washington, D.C., for his 85th birthday — to see the Iwo Jima memorial. It was the same week that the movie “Flags of Our Fathers” came out in theaters.

It was announced on the bus on the way to the memorial, Lake said, that her father was at the Battle of Iwo Jima and saw the flag on Mount Suribachi.

Everyone on the bus, she said, “stood up and clapped for my dad.”