By The Herald Editorial Board

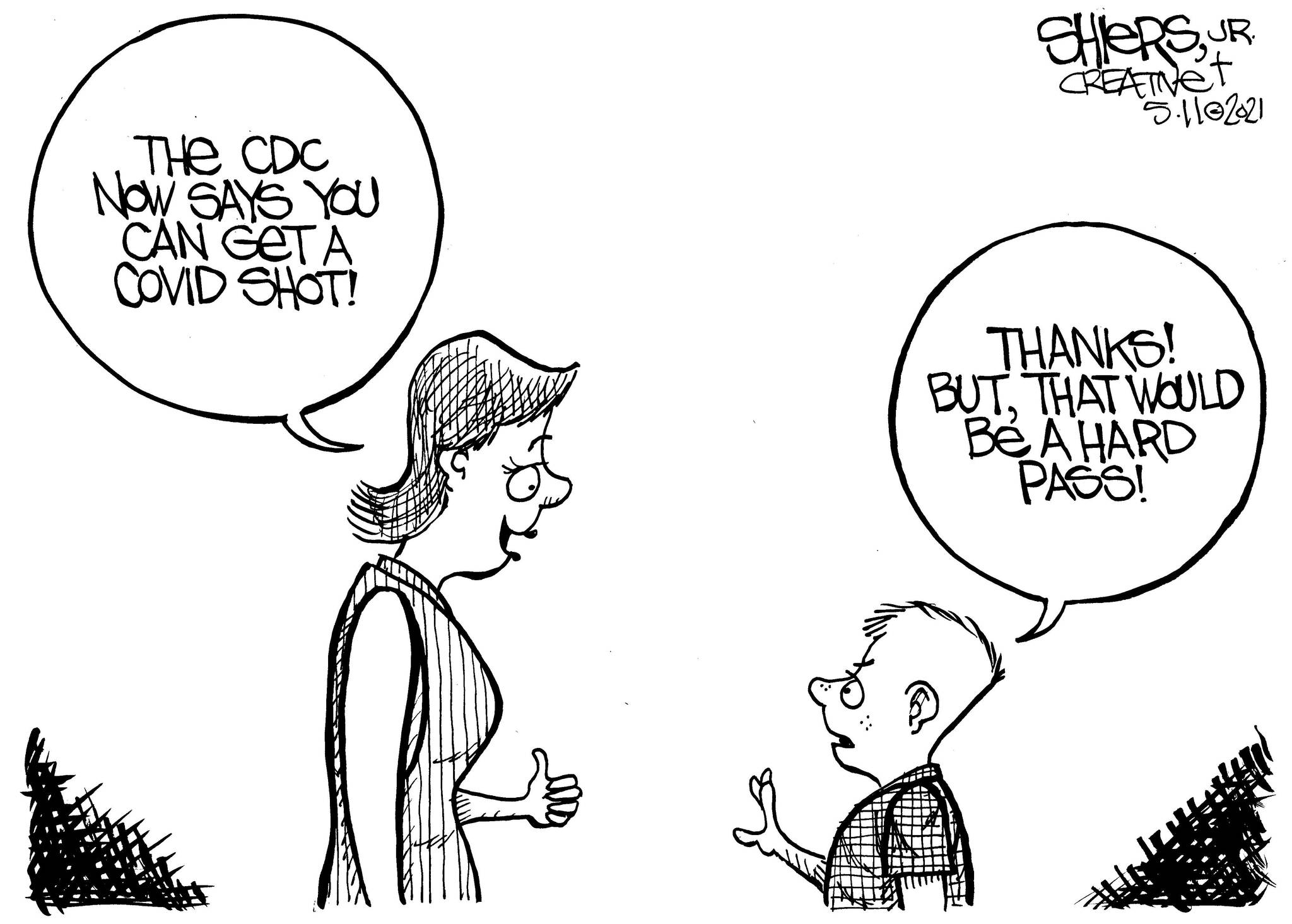

For many parents, the question no longer is hypothetical and can no longer be avoided: Will you have your children vaccinated against COVID-19?

Earlier in the week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared the use of the vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech for children ages 12 to 15, the same findings it had made earlier for those 16 and older. That determination was followed Wednesday by the endorsement of the vaccine for that age group by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advisory committee on immunization practices. The vaccine will now be made available to everyone in the United States 12 and older.

Similar authorization could follow soon for the other two vaccines now approved for adults from Moderna and Johnson & Johnson. No timeline has been announced for approval for vaccines for children 11 or younger.

The most recent authorization for the Pfizer vaccine follows the review of trials of more than 2,000 children in that age group, with about half receiving the vaccine and less than half receiving a placebo. The trials found the vaccine 100 percent effective for the age group, confirming no cases of COVID-19 infections among those who were inoculated, while 16 of the 970 receiving the placebo contracted the diseases, according to a report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, which joined the CDC in support of the vaccine for youths 12 and older.

As with adults, the most common side effects were pain where the injection was given, short-lived fatigue, headache, chills, muscle pain, fever and joint pain for some. And as with adults, youths will get two doses of the same vaccine 21 days apart. Adolescents also can receive the COVID vaccine at the same time as vaccinations for other childhood diseases.

For children, who have gone more than a year separated from friends, activities and in-person school, the vaccine “will decrease transmission within their families, and it will contribute to community immunity and allow kids to more safely go back to camps this summer and back to in-person school,” said Dr. Henry Bernstein, a professor of pediatrics at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell and a member of the CDC’s immunization practices panel.

But unlike other vaccines for childhood diseases, the COVID vaccine won’t be a prerequisite to attend public schools in Washington state, at least for the time being.

The state Board of Health, which oversees vaccine policy, won’t consider adding it to the list of required vaccinations until it has full authorization from the FDA, a board spokesperson announced this month, according to a Seattle Times report.

As with the agencies’ approvals for the vaccines for adults, none of the vaccines has yet received full FDA approval; instead the vaccines have been granted what’s called “emergency use authorization.” In the interest of getting the vaccines out to the public quickly to better control the pandemic’s spread and limit illness, hospitalizations and deaths, the FDA approved their emergency use — a policy in place since 2001 — following studies and review of data that significantly proved the vaccines’ safety and efficacy but still lands short of more detailed and lengthy reviews mandated for a drug’s full authorization.

Respecting that distinction was the right call by the Board of Health. States, as part of U.S. Supreme Court precedent, can require immunization against childhood diseases for those attending public school, with allowances for allergies and other exemptions, but that requirement might not survive a court challenge without full federal approval of a vaccine, as is the case with other childhood vaccines.

Still, the lack of a requirement for a COVID vaccine is likely to cut the numbers of children returning to classrooms and other activities who have the protection of the vaccine.

A recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, asked parents if they would have their child vaccinated. About 29 percent of parents for all age groups said they would get their kids vaccinated immediately, while 32 percent said they’d wait to see how the vaccine was working. About 19 percent — nearly 2 in 10 parents — said they would not vaccinate their children against COVID; leaving a full 15 percent of parents who would decline unless their school required it, including nearly 1 in 4 parents of children 5 and younger and nearly 1 in 5 parents with kids between 6 and 11 years of age.

It’s significant that those 15 percent of parents could bring vaccination levels to just over 80 percent for children, a figure that could provide a level of community immunity in schools that would best protect those who for health reasons can’t receive a COVID vaccination.

It’s understandable that parents might be more hesitant about their children receiving the vaccine than they might be for themselves.

While children have shown lower incidences of COVID and fewer severe outcomes, children are not immune and accounted for a growing number of weekly COVID cases between last summer and the end of last year, according to the CDC.

Since the pandemic began, and as of May 6, more than 3.85 million children have tested positive for COVID-19, and following earlier decreases in weekly cases among children, counts have now topped 72,000 in recent weeks. And the CDC warns that COVID’s longer-term impacts on children’s health are unknown and need further study.

This makes it all the more important for those parents who accept the safety and efficacy of vaccines for the coronavirus to get their children immunized now if they are 12 and older, and as soon as available for younger children. Those waiting for a mandate should reconsider.

This editorial was produced by The Daily Herald (Everett) Editorial Board. The Herald is a sister newspaper of the Mercer Island Reporter.