One of the most-loved hymns of all time was inspired by a tragic accident that took place one-hundred-fifty years ago this month. But to appreciate the rest of the story, you have to picture what took place two years prior.

As Horatio Spafford sat with his wife, Anna, and their four daughters at Thanksgiving in November 1871, he had to think twice when asked to pass the sugar bowl. Life had been anything but sweet in recent weeks. On October 9th, the successful Chicago attorney anxiously watched as wind-swept flames swallowed up ten square blocks of office buildings and homes along Lake Michigan. Among the smoldering ash heaps were several of Spafford’s prized investment properties.

The God-fearing lawyer, who was a personal friend of evangelist Dwight L. Moody, had lost a fortune. It is also quite likely that the words of the apostle Paul stuck in Horatio’s throat while he swallowed his turkey dinner: “Give thanks in everything; for this is God’s will for you…” (1 Thess. 5:18).

How could he be grateful when life was anything but sweet? But as he looked around the family table at his beloved Anna and his four darling daughters, Spafford realized his true wealth had not gone up in smoke. He sensed the presence of a faithful God. How very grateful he was for a godly wife who was teaching their girls to love Jesus. But two short years later, Horatio sat alone at an empty Thanksgiving table. No turkey or pumpkin pie. No appetite. A grateful, yet broken heart once again pulsated with pain. And thus begins “the rest of the story.”

In an effort to move beyond the devastation surrounding their financial ruin from the Great Chicago Fire, the Spaffords had planned an extended family vacation in England. The family of six had traveled by train to New York to board a ship. Sadly, unexpected business dealings had required Horatio to return to Chicago just as the family was about to embark. He had waved good-bye to his wife and four girls, ages 2 to 11, as the Ville du Havre sailed out of New York harbor toward England. He had assured them he would join them in a few weeks.

And then the unthinkable. The vessel had collided with another ship in the North Atlantic. Within twelve minutes the Ville du Havre had sunk as 226 passengers lost their lives. Although many, including Horatio’s wife, had been saved by the crew of another ship, all four Spafford daughters had drowned. Upon reaching England, Anna had sent her husband a telegram. As Horatio sat alone on Thanksgiving 1873, he could only ponder his wife’s telegram summarized by two words: Saved alone.

In his grief, he was grateful his sweetheart had been spared. He gave thanks that all his girls were safe with Jesus now. He found the inner strength to celebrate that God was in control. Having sensed God’s peace in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire two years earlier, he had learned that the granules of God’s grace could sweeten the bitter taste of tragedy. Beneath the ache of his broken heart, he felt an unexplainable peace. In the depth of his soul, all was well.

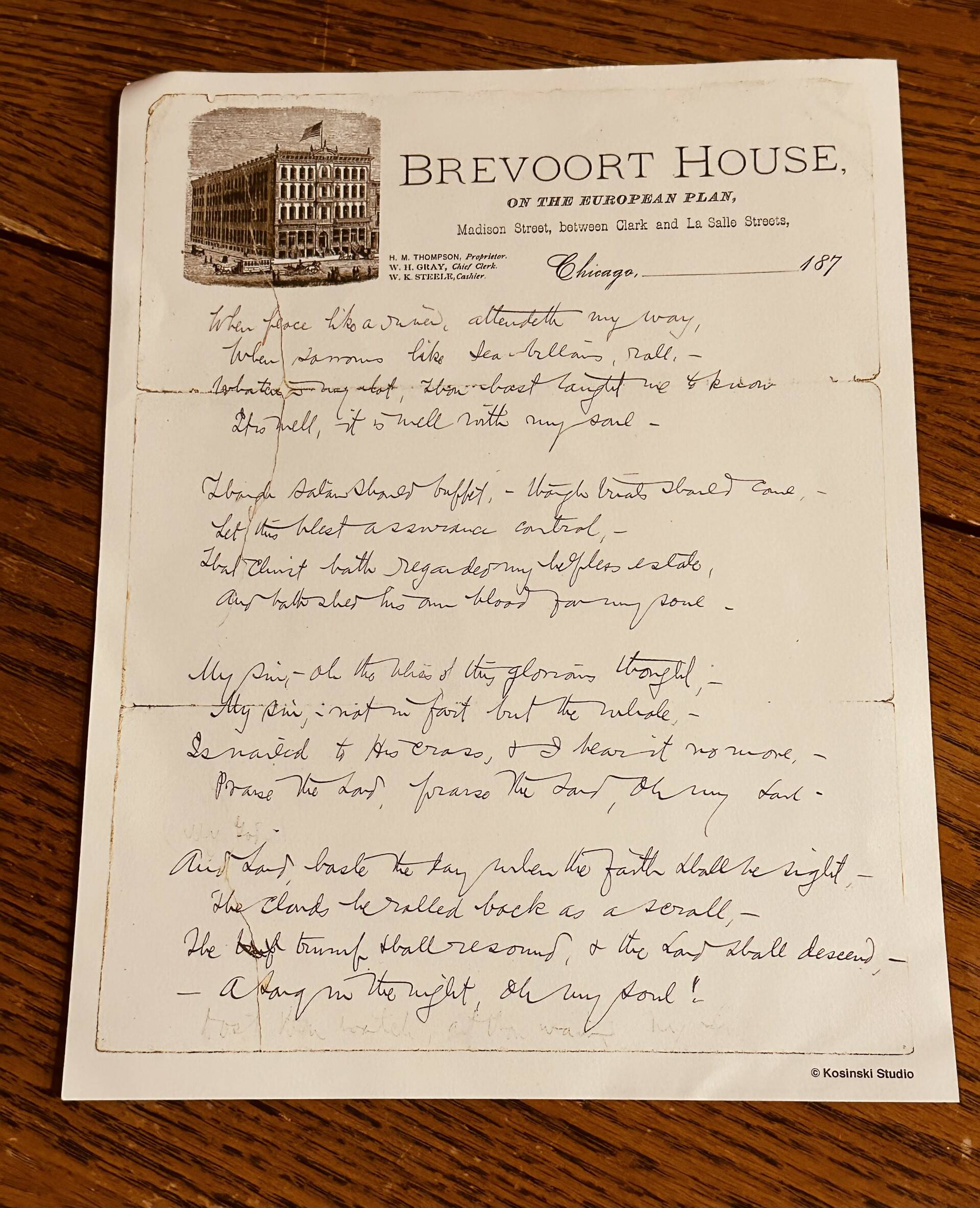

Spafford booked passage for England to join Anna. When the ship sailed near the area where the Ville du Havre had gone down, Horatio stood on the deck looking out at the icy and angry ocean. Reaching into his coat pocket and finding a sheet of hotel stationery, he proceeded to pen a poem articulating his emotions. Little did he realize his lines would be sung as a hymn in churches for generations to come: “When peace, like a river, attendeth my way, When sorrows like sea billows roll; Whatever my lot, Thou has taught me to say, It is well, it is well with my soul.”

As I anticipate a gathering around the Thanksgiving table later this month, I plan to read aloud the lyrics of “It Is Well with My Soul.” Might you consider doing the same? The words born out of heartache continue to nourish the faith of those grateful for God’s blessings in a less-than perfect world.

Guest columnist Greg Asimakoupoulos is a former chaplain at Covenant Living at the Shores in Mercer Island.