You most likely have heard the expression “six degrees of separation.” Well, you don’t have to be Kevin Bacon to appreciate the truth of what that means. I recently experienced those six degrees first-hand.

My wife and I visited Port Townsend a couple weeks back for a three-day getaway with close friends. Following coffee and scones on the waterfront, we walked the main street. Having read Daniel Brown’s book “The Boys in the Boat,” I was fascinated with the Pocock boat house and the vintage rowing shells adjacent to the wooden boat museum. And the vintage architecture of the buildings downtown were a feast for the eyes.

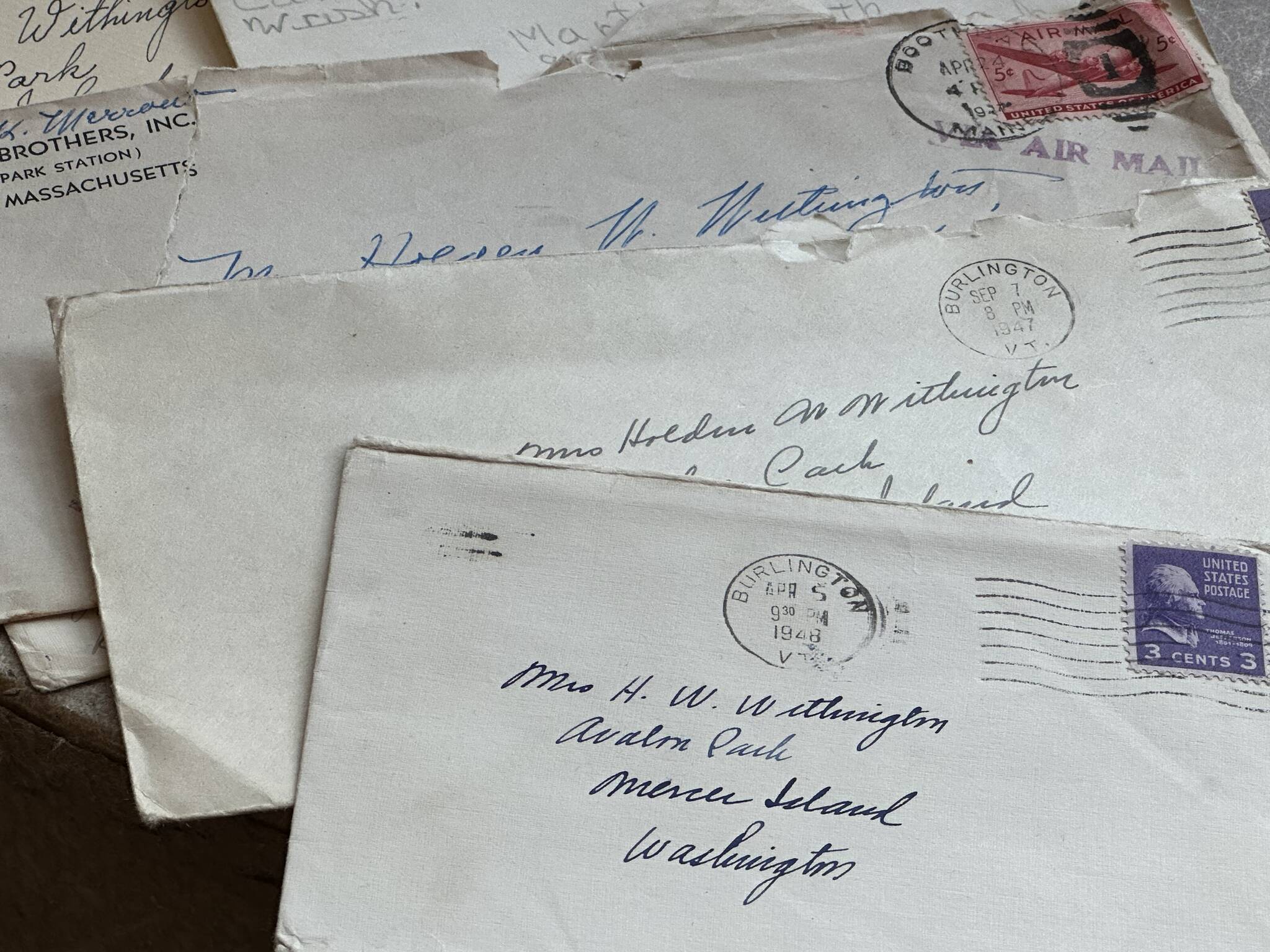

When I happened into a quaint antique store, I saw a basket filled with what appeared to be old handwritten letters. As one who has a prized stamp collection, I couldn’t resist exploring the contents. What I discovered were scores of hand-addressed envelopes with canceled stamps. The letters had been removed to protect the family’s privacy.

Sorting through the pile, I saw many envelopes addressed to a family on Mercer Island. Since that is where I live, my interest increased. The postmark of the first envelope I investigated indicated the letter was sent from Burlington, Vermont on April 5, 1948 to a Mrs. H. W. Withington on Mercer Island. The last name seemed vaguely familiar. The address simply read Avalon Park. That was a neighborhood near to the retirement community where I’ve been the chaplain for the past decade. Since there was no street address, I assumed the home belonged to a prominent family.

I did some quick investigative research on my iPhone. Google gave me what I was looking for. Holden Withington and his wife Betsy were indeed prominent Mercer Island residents. They moved to the island in 1941 (just a year after the floating bridge was completed). Holden, an MIT grad, had been recruited by Boeing as an engineer. He would rapidly climb the ranks of the airplane company eventually retiring as vice-president of engineering.

But Holden’s most notable claim to fame took place in 1948 when the envelope that first caught my eye was addressed. Seventy-five years ago, Holden (who went by Bob) holed-up in a hotel room with five others to design the swept-wing B-52 aircraft. An airplane that would serve the United States military operations for half a century and would serve as the prototype for the Boeing 707.

As I continued my research about the Withington family, I discovered that Bob and Betsy would eventually move into Covenant Shores. What? That’s where I would work for ten years. Even though they both died before I began as chaplain, that is why their name sounded familiar to me. When Bob passed, he was the last surviving member of the team of six who had designed the B-52. His wife would die two weeks before I started working at the Shores.

I also discovered that the Withingtons’ neighbor at Covenant Shores was General Guy Townsend. What? This brigadier general, test pilot and combat veteran had been a friend of mine and fellow Rotarian before he died. And I had the privilege of being chaplain to Guy’s widow Anne until my retirement this summer.

As my iPhone investigation into the past concluded, I came to see that both the Withingtons and the Townsends were more than just neighbors. Their lives were bookends of sorts. Whereas Bob had helped design the B-52, Guy had been at the controls of the very first B-52 when it took off on its test flight from Boeing field enroute for Larson Air Force Base in Moses Lake on April 15, 1952 (three days before I was born). And get this. Both men died in 2011.

Who would have guessed that glancing into that basket of envelopes at that Port Townsend antique shop would find me connecting so many dots? Certainly not me. But it got me reflecting on how small our world really is. And as the Frank Capra movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” celebrates, each human life impacts another in significant (in not always apparent) ways. It pays to be aware!

Guest columnist Greg Asimakoupoulos is a former chaplain at Covenant Living at the Shores in Mercer Island.