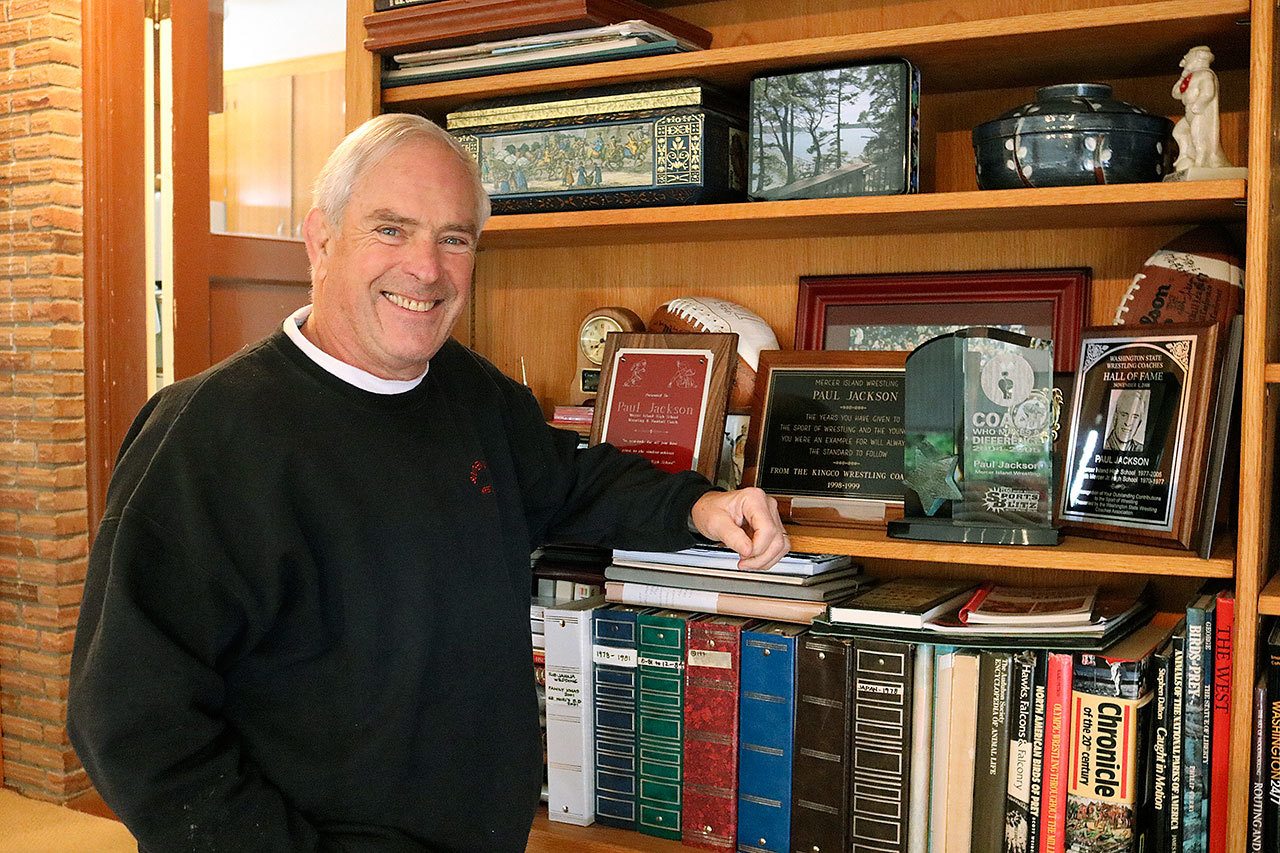

Paul Jackson’s living room in his Mercer Island home has a shelf devoted to the trophies he’s accumulated over his decades-long coaching career, from his 27 years coaching Mercer Island High School wrestling or keepsakes that mark team accomplishments from his 22 years serving as a defensive coordinator under Dick Nicholl for the Mercer Island football team.

Among his prized possessions is Joe De Sena’s 2016 book “Spartan Fit!” The book is a training and diet guide to De Sena’s Spartan Races, though it’s the book’s prologue that hits home with Jackson. It details an incident that took place in the ‘90s, when Jackson’s son, Jay, was woken in the middle of the night in his Palo Alto home by an intruder. Jay was blindfolded, bound and gagged at gunpoint.

“That [prologue] gives you a little bit about some of my thinking about wrestling,” Jackson says. “We both believe it saved [Jay’s] life.”

Miraculously, Jay managed to fend off his intruder. During the unimaginably terrifying conditions of fighting for his life, Jay reverted back to a childhood memory of his father making him wrestle his older brother in their basement — blindfolded, with his father barking for him to fight back.

“If you practice in tougher conditions, the match will seem easy,” Jackson is quoted in the prologue.

Such practices may be interpreted as those of a crazed disciplinarian — until you consider the stakes and the results. Jackson’s wrestling teams certainly got results, for which he is still garnering recognition.

In March, Jackson will be inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame for his lifetime service to the sport of wrestling. It will mark Jackson’s third Hall of Fame induction, though his first on a national level. He is also a member of the Mercer Island High School Sports Hall of Fame and the Washington State Wrestling Coaches Association Hall of Fame.

Jackson’s career includes 36 years of coaching wrestling. He competed at the collegiate level for four years at the University of Washington, then spent three years as an assistant coach at Skagit Valley Junior College as well as the UW.

Jackson began coaching on Mercer Island in 1970 at South Mercer Junior High, where he coached for seven seasons. He became the head wrestling coach at the high school in the fall of 1977.

During Jackson’s tenure at Mercer Island High School, the Islanders won five league championships, were regional champions and placed fourth at the state tournament in 1983. Jackson coached four state champions and 37 state placers, with 22 of his wrestlers continuing on to compete at the college level.

Beyond high school coaching, Jackson coached cultural exchange teams to Japan and Mexico and hosted three exchange teams at Mercer Island. He coached at the Washington Centennial Games in 1989 and the Washington Team at the Junior Nationals in 1989 and 1990.

Jackson has remained active in retirement, refereeing and serving as a state tournament officials evaluator for the past seven years. He was an official from 1966-1980 and picked up the whistle again in 2005 after retiring from coaching.

Being recognized by the National Hall of Fame is a big deal to Jackson, even though he didn’t initially make much of a commotion about the news.

“He was humble,” said Terry Jackson, Jackson’s wife of 50 years. “He kept it to himself for some reason for a while, even from the kids.”

“I figured people find out in due time,” he said. “I don’t need to broadcast it.”

Jackson said De Sena’s prologue account is mostly accurate, though he said he didn’t have his boys wrestle blindfolded in the basement. But Jackson, who was a Green Beret in the Armed Forces, wasn’t against taking away the vision of his wrestlers during training. He said his primary goal was to teach his wrestlers self-reliance and accountability.

“I always had the wrestlers wrestle with their eyes closed because you don’t need to see when you get your orientation,” he said. “You know a leg is here, you know a guy’s head is up here. You don’t necessarily have to see what’s going on, so the more you get in wrestling to just reaction and knowing exactly what to do because you’ve done it so many times, you become a pretty decent wrestler.”

Creighton Laughary coached under Jackson for five seasons before taking over the Mercer Island wrestling program in 2006 until he stepped down last year. He called Jackson an “unfailing advocate” for his athletes and said Jackson created a foundation that instills pride in Mercer Island wrestlers.

“Really everything I know about coaching, I attribute to Paul,” Laughary said.

Of Laughary’s memories working under Jackson, he said one that stuck out was an instance where the coaches were having trouble with one of the wrestlers on the team. As a new teacher and a new coach, Laughary’s initial approach was to kick the kid off the team.

“Paul said something to the effect of, ‘The wrestling team needs the kid, but sometimes the kid needs the wrestling team,’” he recalled. “That’s stuck with me and I‘ve passed that on.”

While Jackson attests that Mercer Island was never a “wrestling hotbed,” he never left to coach in communities where the sport might be more of a priority. Instead, Jackson brought the big name wrestlers to the Island. Jackson hosted the Ed Banach Clinic at MIHS in 1985 and 1988, and the Dave Schultz Clinic in 1984.

“I never felt that there wasn’t enough wrestling here to be a serious contender for state titles,” he said.

Jackson and his wife have lived in the same home on Mercer Island since 1973. Both worked at Mercer Island High School, Jackson as a PE teacher and his wife as a fiscal secretary in the business office. Jackson retired from teaching and coaching in 1999 due to a battle with prostate cancer, but returned to coach wrestling in the fall of 2000.

Jackson and his wife raised three children: Jeff, Janna and Jay, and all three were involved in wrestling. The two boys wrestled while Janna worked as a scorekeeper. All three went to Mercer Island High School and went on to graduate from Stanford University.

Not everything was easy. Both Jackson and his wife acknowledged that being married to a wrestling lifer could be trying. But Terry Jackson adds that life has never been boring.

“Someone expressed to me that there are people out there who don’t have passions, and you have to celebrate the people who have passions,” she said. “He definitely has them.”

“My wife has been an inspiration and a good sport all these years,” Jackson said. “It took a lot of time, I went to a lot of tournaments. When I could and it wasn’t too boring to her, we incorporated the whole family. Some of those tournaments were really long. We wouldn’t get out of there until midnight and some of them wouldn’t even be over.”

Jackson said being inducted into the Hall of Fame was never the goal. He simply loved the challenging sport that he believed could bring out the best of its participants. One never knew when they might need it to save their life.

“We tried to make it hard. I would tell [the kids] when they’d come in, ‘This is the hardest thing you’re ever gonna do physically and maybe mentally,’” Jackson said. “There’s a lot to be learned and part of it is when you lose, in wrestling, you’ve got nobody to blame. It all hinges on that individual.”

When asked what he would want his enduring legacy to be, Jackson lets out a sigh and goes silent for a moment. He says he doesn’t know. Then, he relays an old story from driving around with a parent of three wrestlers who went through the Mercer Island program way back when.

“We were up in Sequim and we drove by his old coach’s house. He pointed it out to me and said, ‘My old coach used to live there,’” Jackson recalled. “He didn’t say a lot about him, but just the fact that he would point it out to me [showed] that the man had some importance in his life. I guess maybe if somebody’s going down 86th and tells their kid, ‘Hey, Coach Jackson lives there,’ that would make me feel pretty good.”